USS Chesapeake (1799)

USS Chesapeake, painting by F. Muller (early 1900s)

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | USS Chesapeake |

| Namesake | Chesapeake Bay[1] |

| Ordered | 27 March 1794 |

| Builder | Josiah Fox |

| Cost | $220,677 |

| Laid down | 10 December 1798[2] |

| Launched | 2 December 1799 |

| Commissioned | 22 May 1800 |

| Captured | 1 June 1813 |

| Name | HMS Chesapeake |

| Acquired | 1 June 1813 by capture |

| Decommissioned | 1819 |

| Fate | Sold for timber |

| General characteristics (1813) | |

| Class and type | 38-gun frigate[Note 1] |

| Tonnage | 1,244[3] |

| Length | 152 ft (46 m), 6 inches lpp[4] |

| Beam | 41.3 ft (12.6 m) or 40 feet, 11 inches[5] |

| Draft | 20 ft (6.1 m)[1] |

| Depth of hold | 13.9 ft (4.2 m)[6] |

| Decks | Orlop, Berth, Gun, Spar |

| Propulsion | Sail |

| Complement | 340 officers and enlisted[6] |

| Armament |

|

Chesapeake was a 38-gun wooden-hulled, three-masted heavy frigate of the United States Navy. She was one of the original six frigates whose construction was authorized by the Naval Act of 1794. Joshua Humphreys designed these frigates to be the young navy's capital ships. Chesapeake was originally designed as a 44-gun frigate, but construction delays, material shortages and budget problems caused builder Josiah Fox to alter his design to 38 guns. Launched at the Gosport Navy Yard on 2 December 1799, Chesapeake began her career during the Quasi-War with France and later saw service in the First Barbary War.

On 22 June 1807 she was fired upon by HMS Leopard of the Royal Navy for refusing to allow a search for deserters. The event, now known as the Chesapeake–Leopard affair, angered the American public and government and was a precipitating factor that led to the War of 1812. As a result of the affair, Chesapeake's commanding officer, James Barron, was court-martialed and the United States instituted the Embargo Act of 1807 against the United Kingdom.

Early in the War of 1812 she made one patrol and captured five British merchant ships. She was captured by HMS Shannon shortly after sailing from Boston, Massachusetts, on 1 June 1813. The Royal Navy took her into their service as HMS Chesapeake, where she served until she was broken up and her timbers sold in 1819. They gave form and structure to the Chesapeake Mill in Wickham, England.

Design and construction

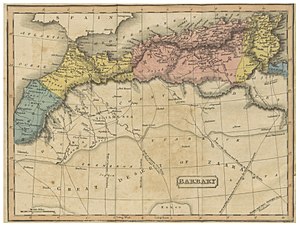

[edit]American merchant vessels began to fall prey to Barbary Pirates, mainly from Algiers, in the Mediterranean during the 1790s. Congress responded with the Naval Act of 1794.[8] The act provided funds for the construction of six frigates, and directed that the construction would continue unless and until the United States agreed peace terms with Algiers.[9][10]

Joshua Humphreys' design was long on keel and narrow of beam (width) to allow for the mounting of very heavy guns. The design incorporated a diagonal scantling (rib) scheme to limit hogging (warping) and included extremely heavy planking. This gave the hull greater strength than those of more lightly built frigates. Since the fledgling United States could not match the number of ships of the European states, Humphreys designed his frigates to be able to overpower other frigates, but with the speed to escape from a ship of the line.[11][12][13]

Originally designated as "Frigate D", the ship remained unnamed for several years. Her keel was laid down in December 1795 at the Gosport Navy Yard in Norfolk County – now the city of Portsmouth in Hampton Roads, Virginia, where Josiah Fox had been appointed her naval constructor and Richard Dale as superintendent of construction. In March 1796 a peace accord was announced between the United States and Algiers and construction was suspended in accordance with the Naval Act of 1794. The keel remained on blocks in the navy yard for two years.[14][15]

The onset of the Quasi-War with France in 1798 prompted Congress to authorize completion of "Frigate D", and they approved resumption of the work on 16 July. When Fox returned to Norfolk he discovered a shortage of timber caused by its diversion from Norfolk to Baltimore in order to finish Constellation. He corresponded with Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert, who indicated a desire to expedite construction of the ship and reduce the overall cost. Fox, always an opponent of Humphreys' large design, submitted new plans to Stoddert which called for utilizing the existing keel but reducing the overall dimensions substantially in length and partially of beam. Fox's plans essentially proposed an entirely different design than originally planned by Humphreys. Secretary Stoddert approved the new design plans.[16][17][18]

When construction finished, Chesapeake had the smallest dimensions of the six frigates. A length of 152.8 ft (46.6 m) between perpendiculars and 41.3 ft (12.6 m) of beam contrasted with her closest sisters, Congress and Constellation, which were built to 164 ft (50 m) in length and 41 ft (12 m) of beam.[16][19][20] The final cost of her construction was $220,677—the second-least expensive frigate of the six. The least expensive was Congress at $197,246.[3]

During construction, a sloop named Chesapeake was launched on 20 June 1799 but was renamed Patapsco between 10 October and 14 November, apparently to free up the name Chesapeake for "Frigate D".[21] In communications between Fox and Stoddert, Fox repeatedly referred to her as Congress, further confusing matters, until he was informed by Stoddert the ship was to be named Chesapeake, after Chesapeake Bay.[1] She was the only one of the six frigates not named by President George Washington, nor after a principle of the United States Constitution.[16][22]

Armament

[edit]Chesapeake's nominal rating is stated as either 36 or 38 guns.[Note 1] Originally designated as a 44-gun ship, her redesign by Fox led to a rerating, apparently based on her smaller dimensions when compared to Congress and Constellation. Joshua Humphreys may have rerated Chesapeake to 38 guns,[26] or Secretary Stoddert may have rerated Congress and Constellation to 38 guns because they were larger than Chesapeake, which was rated to 36 guns.[23] The most recent information on her rating is from the Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, published in 2011, which states she was rerated "from 44 guns to 36, eventually increased to 38".[1] Her gun rating remained a matter of confusion throughout her career; Fox used a 44-gun rating in his correspondence with Secretary Stoddert.[22] In preparing for the War of 1812 Secretary of the Navy Paul Hamilton directed Captain Samuel Evans to recruit the number of crewmen required for a 44-gun ship. Hamilton was corrected by William Bainbridge in a letter stating, "There is a mistake in the crew ordered for the Chesapeake, as it equals in number the crews of our 44-gun frigates, whereas the Chesapeake is of the class of the Congress and Constellation."[29] Letters between Stoddert, Fox, and others dated 26 October, 1799 it was stated she was supposed to have 28 18 pounders and 16 9 pounders, but was revised at an unknown point to 30 18 pounders and 14 12 pounders. The change was cancelled. There was a question as to the gun deck being pierced for 28 or 30 guns.[30] When sold for scrap by the Royal Navy in 1819, she was rated as a 48-gun ship.[31]

Gun ratings did not correspond to the actual number of guns a ship would carry. Chesapeake was noted as carrying 40 guns during her encounter with HMS Leopard in 1807 and 50 guns during her engagement with HMS Shannon in 1813. The 50 guns consisted of twenty-eight 18-pounder (8 kg) long guns on the gun deck, fourteen on each side. This main battery was complemented by two long 12-pounders (5.5 kg), one long 18-pounder, eighteen 32-pounder (14.5 kg) carronades, and one 12-pound carronade on the spar deck. Her broadside weight was 542 pounds (246 kg).[7][32]

The ships of this era had no permanent battery of guns; guns were completely portable and were often exchanged between ships as situations warranted. Each commanding officer modified his vessel's armament to his liking while taking into consideration factors such as the overall tonnage of cargo, complement of personnel aboard, and planned routes to be sailed. Consequently, a vessel's armament would change often during its career; records of the changes were not generally kept.[33]

Quasi-War

[edit]Chesapeake was launched on 2 December 1799 during the undeclared Quasi-War (1798–1800), which arose after the French navy seized American merchant ships. Her fitting-out continued until May 1800. In March Josiah Fox was reprimanded by Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert for continuing to work on Chesapeake while Congress, still awaiting completion, was fully manned with a crew drawing pay. Stoddert appointed Thomas Truxton to ensure that his directives concerning Congress were carried out.[34]

Chesapeake first put to sea on 22 May commanded by Captain Samuel Barron and marked her departure from Norfolk with a 13-gun salute.[35] Her first assignment was to carry currency from Charleston, South Carolina, to Philadelphia.[36] On 6 June she joined a squadron patrolling off the southern coast of the United States and in the West Indies escorting American merchant ships.[37]

Capturing the 16-gun French privateer La Jeune Creole on 1 January 1801 after a chase lasting 50 hours, she returned to Norfolk with her prize on 15 January. Chesapeake returned briefly to the West Indies in February, soon after a peace treaty was ratified with France. She returned to Norfolk and decommissioned on 26 February, subsequently being placed in reserve.[1][38]

First Barbary War

[edit]

During the Quasi-War, the United States had paid tribute to the Barbary States to ensure that they would not seize or harass American merchant ships.[39] In 1801 Yusuf Karamanli of Tripoli, dissatisfied with the amount of tribute he received in comparison to that paid to Algiers, demanded an immediate payment of $250,000.[40] Thomas Jefferson responded by sending a squadron of warships to protect American merchant ships in the Mediterranean and to pursue peace negotiations with the Barbary States.[41][42] The first squadron was under the command of Richard Dale in President. and the second was assigned to the command of Richard Valentine Morris in Chesapeake. Morris's squadron eventually consisted of the vessels Constellation, New York, John Adams, Adams, and Enterprise. It took several months to prepare the vessels for sea; they departed individually as they became ready.[43][44]

Captain Thomas Truxton was ordered to take command of Chesapeake on 12 January, 1802 by the Secretary of the Navy.[45] He proposed that he should be squadron commander of the new squadron leaving for the Mediterranean, or he should leave the service, in a letter to Secretary of the Navy dated 3 March, 1802.[46] Secretary of the Navy ordered Capt. Richard V. Morris to take command of Chesapeake in a letter dated 11 March, 1802.[47] Truxton was relieved of command by the Navy Secretary in a letter dated 13 March with Lt. William Smith taking temporary command.[48] Chesapeake sailed from Hampton Roads on 27 April 1802 and arrived at Gibraltar on 25 May; she immediately put in for repairs, as her main mast had split during the voyage.[49] Morris remained at Gibraltar while awaiting word on the location of his squadron, as several ships had not reported in. On 22 July Adams arrived with belated orders for Morris, dated 20 April. Those were to "lay the whole squadron before Tripoli" and negotiate peace.[50] Chesapeake and Enterprise departed Gibraltar on 17 August bound for Leghorn, while providing protection for a convoy of merchant ships that were bound for intermediate ports. Morris made several stops in various ports before finally arriving at Leghorn on 12 October, after which he sailed to Malta. Chesapeake undertook repairs of a rotted bowsprit.[51][52] Chesapeake was still in port when John Adams arrived on 5 January 1803 with orders dated 23 October 1802 from Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith. These directed Chesapeake and Constellation to return to the United States; Morris was to transfer his command to New York.[53] Constellation sailed directly as ordered, but Morris retained Chesapeake at Malta, claiming that she was not in any condition to make an Atlantic voyage during the winter months.[54]

Morris now had the ships New York, John Adams, and Enterprise gathered under him, while Adams was at Gibraltar.[54] On 30 January Chesapeake and the squadron got underway for Tripoli, where Morris planned to burn Tripolitan ships in the harbor. Heavy gales made the approach to Tripoli difficult. Fearing Chesapeake would lose her masts from the strong winds, Morris returned to Malta on 10 February.[55][56] With provisions for the ships running low and none available near Malta, Morris decided to abandon plans to blockade Tripoli and sailed the squadron back to Gibraltar for provisioning. They made stops at Tunis on 22 February and Algiers on 19 March. Chesapeake arrived at Gibraltar on 23 March, where Morris transferred his command to New York.[57] Under James Barron, Chesapeake sailed for the United States on 7 April and she was placed in reserve at the Washington Navy Yard on 1 June, 1803.[58]

Morris remained in the Mediterranean until September, when orders from Secretary Smith arrived suspending his command and instructing him to return to the United States. There he faced a Naval Board of Inquiry which found that he was censurable for "inactive and dilatory conduct of the squadron under his command". He was dismissed from the navy in 1804.[59][60] Morris's overall performance in the Mediterranean was particularly criticized for the state of affairs aboard Chesapeake and his inactions as a commander. His wife, young son, and housekeeper accompanied him on the voyage, during which his wife gave birth to another son. Midshipman Henry Wadsworth wrote that he and the other midshipman referred to Mrs. Morris as the "Commodoress" and believed she was the main reason behind Chesapeake remaining in port for months at a time.[61][62] Consul William Eaton reported to Secretary Smith that Morris and his squadron spent more time in port sightseeing and doing little but "dance and wench", rather than blockading Tripoli.[63]

Chesapeake–Leopard Affair

[edit]

In January 1807 Master Commandant Charles Gordon was appointed Chesapeake's commanding officer (captain). He was ordered to prepare her for patrol and convoy duty in the Mediterranean to relieve her sister ship Constitution, which had been on duty there since 1803. James Barron was appointed overall commander of the squadron as its commodore.[64][65] Chesapeake was in much disarray from her multi-year period of inactivity and many months were required for repairs, provisioning, and recruitment of personnel.[66] Lieutenant Arthur Sinclair was tasked with the recruiting. Among those chosen were three sailors who had deserted from HMS Melampus. The British ambassador to the United States requested the return of the sailors. Barron found that, although they were indeed from Melampus, they had been impressed into Royal Navy service from the beginning. He therefore refused to release them back to Melampus and nothing further was communicated on the subject.[67][68]

In early June Chesapeake departed the Washington Navy Yard for Norfolk, Virginia, where she completed provisioning and loading armaments. Captain Gordon informed Barron on the 19th that Chesapeake was ready for sea and they departed on 22 June armed with 40 guns.[32] At the same time, a British squadron consisting of HMS Melampus, Bellona, and Leopard (a 50-gun fourth rate) were lying off the port of Norfolk blockading two French ships there. As Chesapeake departed, the squadron ships began signaling each other and Leopard got under way, preceding Chesapeake to sea.[67][69]

After sailing for some hours, Leopard, commanded by Captain Salusbury Humphreys, approached Chesapeake and hailed a request to deliver dispatches to England, a customary request of the time.[70] When a British lieutenant arrived by boat he handed Barron an order, given by Vice-Admiral George Berkeley of the Royal Navy, which instructed the British ships to stop and board Chesapeake to search for deserters. Barron refused to allow this search, and as the lieutenant returned to Leopard Barron ordered the crew to general quarters.[71] Shortly afterward Leopard hailed Chesapeake; Barron could not understand the message. Leopard fired a shot across the bow, followed by a broadside, at Chesapeake. For fifteen minutes, while Chesapeake attempted to arm herself, Leopard continued to fire broadside after broadside until Barron struck his colors. Chesapeake only managed to fire one retaliatory shot after hot coals from the galley were brought on deck to ignite the cannon.[72] The British boarded Chesapeake and carried off four crewmen, declining Barron's offer that Chesapeake be taken as a prize of war.[73] Chesapeake suffered three sailors killed and Barron was among the eighteen wounded.[74]

Word of the incident spread quickly on Chesapeake's return to Hampton Roads, where the British squadron that included Leopard was provisioning. Mobs of angry citizens destroyed two hundred water casks destined for the squadron and nearly killed a British lieutenant before local authorities intervened. The fourth death of a Chesapeake sailor two days later came in the midst of the growing outrage. The coffin holding the body of Robert MacDonald was transported across the Elizabeth River, which flowed between Portsmouth and Norfolk, amid cannon tributes and ships at half mast and an estimated 4,000 citizens to receive it at the Norfolk wharf.

In subsequent days, the event would lead to the angry resolutions of town governments on the east coast and into the Midwest. In Pennsylvania, a group representing the state's First Congressional District declared the attack "an act of such consummate violence and wrong, and of so barbarous and murderous a character that it would debase and degrade any nation and much more so a nation of freemen to submit to it."

President Jefferson recalled all US warships from the Mediterranean and issued a proclamation: all British warships were banned from entering US ports and those already in port were to depart. The incident eventually led to the Embargo Act of 1807.[75][76] As the first significant conflict between America and Great Britain after the Revolutionary War, it would give energy to what some historians would deem the second Revolutionary War, the War of 1812.[77]

Chesapeake was completely unprepared to defend herself during the incident. None of her guns were primed for operation and the spar deck was filled with materials that were not properly stowed in the cargo hold.[78] A court-martial was convened for Barron and Captain Gordon, as well as Lieutenant Hall of the Marines. Barron was found guilty of "neglecting on the probability of an engagement to clear his Ship for action" and suspended from the navy for five years. Gordon and Hall were privately reprimanded, and the ship's gunner was discharged from the navy.[79][80]

War of 1812

[edit]

After the heavy damage inflicted by Leopard, Chesapeake returned to Norfolk for repairs. Under the command of Stephen Decatur, she made patrols off the New England coast enforcing the Embargo Act throughout 1809.[81]

The Chesapeake–Leopard Affair, and later the Little Belt affair, contributed to the United States' decision to declare war on Britain on 18 June 1812. Chesapeake, under the command of Captain Samuel Evans, was prepared for duty in the Atlantic.[82] Beginning on 13 December, she ranged from Madeira and traveled clockwise to the Cape Verde Islands and South America, and then back to Boston. She captured six ships as prizes: the British ships Volunteer, Liverpool Hero, Earl Percy, and Ellen, the brig Julia (an American ship trading under a British license), and Valeria (an American ship recaptured from British privateers). During the cruise an unidentified British ship-of-the-line and a frigate chased Chesapeake but, after a passing storm squall, the two pursuing ships were gone the next morning. The cargo of Volunteer, 40 tons of pig iron and copper, was sold for $185,000. Earl Percy never made it back to port as she ran aground off the coast of Long Island. Liverpool Hero was burned as she was considered leaky. Chesapeake's total monetary damage to British shipping was $235,675 (equivalent to $4.2 million in 2023). She returned to Boston on 9 April 1813 for refitting.[83][84]

Captain Evans, now in poor health, requested relief of command. Captain James Lawrence, late of Hornet and her victory over HMS Peacock, took command of Chesapeake on 20 May. Matters on board the ship were in disarray. The term of enlistment for many of the crew had expired and they were daily leaving the ship.[84] Those who remained were disgruntled and approaching mutiny, as the prize money they were owed from her previous cruise was held up in court.[85] Lawrence paid out the prize money from his own pocket in order to appease them. Some sailors from Constitution joined Chesapeake and they made up the crew, along with sailors of several nations.[86]

Meanwhile, HMS Shannon, a 38-gun frigate, under Captain Philip Broke was patrolling off the port of Boston on blockade duty. Shannon had been under the command of Broke since 1806 and, under his direction, the crew held daily great gun and small arms drills lasting up to three hours each. Crew members who hit their bullseye were awarded a pound (454 g) of tobacco for their good marksmanship. Broke had also fitted out his cannons with dispart and tangent sights to increase accuracy as well as degree bearings on the decks and gun carriages to allow the crew to focus their fire on a specific target. In this regard Chesapeake, with traditional gun practice and a crew that had only been together for a few months, was inferior.[87]

Chesapeake vs Shannon

[edit]

Lawrence, advised that Shannon had moved in closer to Boston, began preparations to sail on the evening of 31 May. The next morning Broke wrote a challenge to Lawrence and dispatched it to Chesapeake; it had not arrived when Lawrence set out to meet Shannon on his own accord.[88][89]

Leaving port with a broad white flag bearing the motto "Free Trade and Sailors' Rights", Chesapeake met Shannon near 5 pm that afternoon. During six minutes of firing, each ship managed two full broadsides. Chesapeake's first broadside was fired while the ship was heeling, causing most shots to strike the water or Shannon's waterline, causing little damage; although carronade fire caused serious damage to Shannon's rigging.[90] A second round of fire was more effective, landing hits on Shannon's 12-pounder shot locker. Chesapeake's 32-pound carronades punished Shannon's forecastle, killing three men, wounding others and disabling Shannon's nine-pounder bow gun.[91] Chesapeake suffered far more heavily in the exchange, as accurate British fire caused heavy losses among American gun crews, and crippling losses to the men and officers on Chesapeake's quarterdeck. A succession of helmsmen were killed and her wheel was destroyed. At the same time, her foretopsail halyard was shot away causing the ship to lose maneuverability.[92]

Unable to maneuver, Chesapeake "luffed up" and her port stern quarter caught against the side of Shannon amidships and the two ships were lashed together.[93] Confusion and disarray reigned on the deck of Chesapeake; Captain Lawrence tried rallying a party to board Shannon, but the bugler failed to sound the call.[94] At this point a shot from a sniper mortally wounded Lawrence; as his men carried him below, he gave his last order: "Don't give up the ship. Fight her till she sinks."[95][96] There are varying historical accounts of what Lawrence may actually have uttered.[97]

Captain Broke boarded Chesapeake at the head of a party of 20 men. They met little resistance from Chesapeake's crew, most of whom had run below deck. The only resistance from Chesapeake came from her contingent of marines. The British soon overwhelmed them; only nine escaped injury out of 44.[98] Captain Broke was severely injured in the fighting on the forecastle, being struck in the head with a sword. Soon after, Shannon's crew pulled down Chesapeake's flag. Only 15 minutes had elapsed from the first exchange of gunfire to the capture.[99][100]

Reports on the number of killed and wounded aboard Chesapeake during the battle vary widely. Broke's after-action report from 6 July states 70 killed and 100 wounded.[101] Other contemporary sources place the number between 48 and 61 killed and 85–99 wounded.[102][103] Discrepancies in the number of killed and wounded are possibly caused by the addition of sailors who died of their wounds after the battle.[104] The counts for Shannon have fewer discrepancies with 23 killed and 56 wounded.[105] Despite his serious injuries, Broke ordered repairs to both ships and they proceeded on to Halifax, Nova Scotia. Captain Lawrence died en route of his wounds and was buried in a Halifax cemetery with full military honors. The dead crewmen were buried on Dead Man's Island in Nova Scotia. Captain Broke survived his wounds and was later made a baronet.[106][107]

Royal Navy service and legacy

[edit]

The Royal Navy repaired Chesapeake and took her into service as HMS Chesapeake. She served on the Halifax station under the command of Alexander Dixie until 1814, and, in April, was sighted in the Chesapeake Bay, off the coast of Virginia's Eastern Shore.[108] Later that year and under the command of George Burdett she sailed to Plymouth, England, for repairs in October of that year. Afterward she made a voyage to Cape Town, South Africa, until learning of the peace treaty with the United States in May 1815.[109] Later that year a report was made concerning Chesapeake's performance in British service. Her captain observed that she was strongly constructed, but criticized the excessive overhang of the stern. He concluded that she was not a suitable ship to serve as a model for copying. Her speed under sail was not impressive: 9 kn (17 km/h; 10 mph) close-hauled and 11 kn (20 km/h; 13 mph) large.[110]

In 1819, the Chesapeake, constructed in Portsmouth, Virginia, was sold for £500 to Joshua Holmes in Portsmouth, England, and her various components were offered for sale in the Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle, published in Hampshire as a "very large quantity of OAK and FIR TIMBER of most excellent quality, and well worth the attention of any person."[111] Large, unbroken portions of the ship were bought by John Prior to build a new watermill at Wickham, Hampshire.[112][113] The Chesapeake Mill would play a significant role in the agricultural economy of Hampshire until it became increasingly obsolescent in the 1970s. After failed attempts to preserve the mill as a historical center through the early 2000s, it was given over to commercial operators and operated as an antique mall in 2021.

As a watermill, the Chesapeake may be the most originally preserved of the original six frigates of the U.S. Navy. Interpretation of the USS Constitution, preserved in Boston harbor, suggests original wood or components from 0%[114] to 15%.[115] The Chesapeake Mill is constructed of largely intact and unaltered components of the original ship – timber configuration, lintels, stairways, the five main spine beams to each floor, the floor joists, the roof timbers, other wood – some appearing to show the grapeshot of battle. The wood has been preserved within a five-story building with walls and beneath a roof for 200 years.

In 1996 a timber fragment from the Chesapeake Mill was returned to the United States. It is on display at the Hampton Roads Naval Museum.[116]

Almost from her beginnings, Chesapeake was considered an "unlucky ship", the "runt of the litter" to the superstitious sailors of the 19th century,[117] and the product of a disagreement between Humphreys and Fox. Her unsuccessful encounters with HMS Leopard and Shannon, the courts-martial of two of her captains, and the accidental deaths of several crewmen led many to believe she was cursed.[16][23][25]

Arguments defending both Humphreys and Fox regarding their long-standing disagreements over the design of the frigates carried on for years. Humphreys disowned any credit for Fox's redesign of Chesapeake. In 1827 he wrote, "She [Chesapeake] spoke his [Fox's] talents. Which I leave the Commanders of that ship to estimate by her qualifications."[118]

Lawrence's last command of "Don't give up the ship!" became a rallying cry for the US Navy. Oliver Hazard Perry, in command of naval forces on Lake Erie during September 1813, named his flagship Lawrence, which flew a broad blue flag bearing the words "Dont give up the ship!" The phrase is still used in the US Navy today.[119]

Chesapeake's battle-damaged ensign was sold at auction in London in 1908. Purchased by William Waldorf Astor, it now resides in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England, along with her signal book.[120][121] The Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, Nova Scotia, holds several artifacts from the battle including the mess kettle, and an officers chest from Chesapeake.[122] One of the 18-pounder guns from Chesapeake is mounted beside Province House, the Nova Scotia Legislature.[123]

A fictionalized account of the battle between Chesapeake and Shannon appears at the conclusion of The Fortune of War, the sixth historical novel in the Aubrey-Maturin series by British author Patrick O'Brian, first published in 1979.[124]

In 2021, the U.S. Navy announced that a namesake USS Chesapeake would be constructed as a member of a Constellation-class of ships in future years.[125]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b For purposes of this article, Chesapeake is listed as a 38-gun ship since the majority of references use that number. Stating 36 guns are Allen,[17] Beach,[23] and Maclay and Smith.[24] Those stating 38 guns are Calhoun,[25] Chapelle,[26] Cooper,[27] Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships,[1] Roosevelt,[3] and Toll.[28] Fowler does not mention a rating.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Chesapeake". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ^ "Naval Documents related to the Quasi-War Between the United States and France Volume Part 3 of 3 Naval Operations August 1799 to December 1799, December, p. 472" (PDF). U.S. Government printing office via Imbiblio. Retrieved 30 May 2024.

- ^ a b c Roosevelt (1883), p. 48.

- ^ Naval Documents related to the Quasi-War Between the United States and France (PDF). Vol. VII Part 1 of 4: Naval Operations December 1800-December 1801, December 1800-March 1801. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 365. Retrieved 29 September 2024 – via Ibiblio.

- ^ Naval Documents related to the Quasi-War Between the United States and France (PDF). Vol. VII Part 1 of 4: Naval Operations December 1800-December 1801, December 1800-March 1801. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 365. Retrieved 29 September 2024 – via Ibiblio.

- ^ a b Chapelle (1949), p. 535.

- ^ a b Roosevelt (1883), p. 181.

- ^ Allen (1909), pp. 41–42.

- ^ Beach (1986), p. 29.

- ^ An Act to provide a Naval Armament. 1 Stat. 350 (1794). Library of Congress. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ^ Toll (2006), pp. 49–53.

- ^ Beach (1986), pp. 29–30, 33.

- ^ Allen (1909), pp. 42–45.

- ^ "Navy History: Federal/Quasi War". Naval History & Heritage Command. Archived from the original on 6 February 1997. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ Beach (1986), p. 30.

- ^ a b c d Toll (2006), p. 289.

- ^ a b Allen (1909), p. 56.

- ^ Beach (1986), pp. 30–31.

- ^ "Congress". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ^ "Constellation". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ^ "Patapsco". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ^ a b Beach (1986), p. 31.

- ^ a b c Beach (1986), p. 32.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, p. 158.

- ^ a b Calhoun (2008), p. 6.

- ^ a b Chapelle (1949), p. 128.

- ^ Cooper (1856), p. 134.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 107.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), p. 50.

- ^ "Naval Documents related to the Quasi-War Between the United States and France Volume Part 2 of 3 Naval Operations August 1799 to December 1799, October to November Pg. 327-328" (PDF). U.S. Government printing office via Imbiblio. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ "No. 17494". The London Gazette. 13 July 1819. p. 1228.

- ^ a b Cooper (1856), pp. 225–226.

- ^ Jennings (1966), pp. 17–19.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 138.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 139.

- ^ Cooper (1856), p. 139.

- ^ Allen (1909), p. 217.

- ^ Allen (1909), pp. 217, 252.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 88, 90.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, p. 228.

- ^ Allen (1905), p. 92.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 105–106.

- ^ Cooper (1856), p. 155.

- ^ Naval Documents related to the United States Wars with the Barbary Powers Volume II Part 1 of 3 January 1802 through August 1803 (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 19. Retrieved 27 October 2024 – via Ibiblio.

- ^ Naval Documents related to the United States Wars with the Barbary Powers Volume II Part 1 of 3 January 1802 through August 1803 (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 76. Retrieved 27 October 2024 – via Ibiblio.

- ^ Naval Documents related to the United States Wars with the Barbary Powers Volume II Part 1 of 3 January 1802 through August 1803 (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 82. Retrieved 27 October 2024 – via Ibiblio.

- ^ Naval Documents related to the United States Wars with the Barbary Powers Volume II Part 1 of 3 January 1802 through August 1803 (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 83. Retrieved 28 October 2024 – via Ibiblio.

- ^ Cooper (1856), p. 158.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 113–114.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 114–116.

- ^ Cooper (1856), p. 159.

- ^ Allen (1905), p. 117.

- ^ a b Allen (1905), p. 118.

- ^ Allen (1905), p. 120.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, p. 235.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 121–123.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 133–135.

- ^ Beach (1986), p. 45.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 173.

- ^ Fowler (1984), p. 73.

- ^ Fowler (1984), pp. 74–75.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 290.

- ^ Cooper (1856), p. 224.

- ^ Fowler (1984), p. 152.

- ^ a b Fowler (1984), p. 153.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, pp. 305–306.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 295.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, p. 306.

- ^ Cooper (1856), pp. 227, 229.

- ^ Fowler (1984), p. 155.

- ^ Cooper (1856), p. 230.

- ^ Toll (2006), pp. 295–298.

- ^ Fowler (1984), pp. 155–156.

- ^ Toll (2006), pp. 299, 301.

- ^ Dickon, Chris (2008) pp. 38–47.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 294.

- ^ Fowler (1984), p. 156.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, pp. 307–308.

- ^ Toll (2006), pp. 289, 310.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 402.

- ^ Calhoun (2008), pp. 6–8, 14–16.

- ^ a b Roosevelt (1883), p. 163.

- ^ Cooper (1856), p. 305.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), p. 178.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), pp. 179–180.

- ^ Cooper (1856), p. 304.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), p. 182.

- ^ Andrew Lambert, The Challenge: Britain Against America in the Naval War of 1812, Faber and Faber (2012), p. 172

- ^ Lambert, p. 173

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), pp. 182–183.

- ^ Padfield, pp. 167–171

- ^ Cooper (1856), p. 306.

- ^ Cooper (1856), pp. 305–307.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), p. 184.

- ^ Dickon, Chris (2008) p. 66

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), p. 185.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), pp. 186–187.

- ^ Cooper (1856), p. 307.

- ^ "No. 16750". The London Gazette. 6 July 1813. p. 1330.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, p. 459.

- ^ Beach (1986), p. 110.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 415.

- ^ "No. 16750". The London Gazette. 6 July 1813. p. 1329.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), p. 187.

- ^ Cooper (1856), p. 308.

- ^ Dickon, Chris (2008) p. 77

- ^ Beach (1986), pp. 112–113.

- ^ Gardiner, p. 147

- ^ Dickon, Chris (2008) p. 79

- ^ "The Chesapeake Mill – history" (PDF). The Chesapeake Mill. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ Beach (1986), p. 113.

- ^ https://acbs.org/acbs-boat-classifications-judging-classes/

- ^ https://ussconstitutionmuseum.org/2018/04/13/rebuilt-preserved-restored-uss-constitution-across-the-centuries/

- ^ Clancy, Paul (17 June 2007). "The Little Warship That Never Quite Could". The Virginian Pilot. p. B3.

- ^ Clancy, Paul (16 November 2008). "Frigate Chesapeake Lives On In Old Mill". The Virginian-Pilot. p. B3.

- ^ Toll (2006), pp. 472–473.

- ^ Halstead, Tom (19 May 2013). "The real, shameful story behind 'Don't give up the ship!'". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 14 September 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ "Chesapeake's Flag Stays in England". The New York Times. 24 April 1908. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ Tomlinson, Barbara (21 April 2009). "Don't give up the ship". National Maritime Museum. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ^ Conlin, Dan (1 June 2013). "An Artifact From a Deadly War of 1812 Battle". The Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ Mercer, Keith (7 June 2013). "Defined by how we remember". Halifax Chronicle Herald.

- ^ O'Brian, Patrick, The Fortune of War (W. W. Norton & Company 1979), pp. 301–329

- ^ "SECNAV Names Future Vessels while aboard Historic Navy Ship". United States Navy (Press release).

References

[edit]- Allen, Gardner Weld (1905). Our Navy and the Barbary Corsairs. Boston; New York; Chicago: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 2618279.

- —— (1909). Our Naval War With France. Boston; New York: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1202325.

- Beach, Edward L. (1986). The United States Navy 200 Years. New York: H. Holt. ISBN 0-03-044711-9. OCLC 12104038.

- Calhoun, Gordon. "The Frigate Chesapeake's War of 1812 Raid on British Commerce" (PDF). The Daybook. XIII (II). Norfolk: Hampton Roads Naval Museum. OCLC 51784156. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 May 2011.

- Gardiner, Robert (2000). Frigates of the Napoleonic Wars. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-861-76135-4. OCLC 247335191.

- Chapelle, Howard Irving (1949). The History of the American Sailing Navy; the Ships and Their Development. New York: Norton. OCLC 1471717.

- Cooper, James Fenimore (1856). History of the Navy of the United States of America (Abridged ed.). New York: Stringer & Townsend. OCLC 197401914.

- Dickon, Chris (2008). The Enduring Journey of the USS Chesapeake. Charleston, SC: History Press. ISBN 978-1-59629-298-7.

- Fowler, William M. (1984). Jack Tars and Commodores: The American Navy, 1783–1815. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-35314-9. OCLC 10277756.

- Jennings, John (1966). Tattered Ensign: The Story of America's Most Famous Fighting Frigate, U.S.S. Constitution. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell. OCLC 1291484.

- Maclay, Edgar Stanton; Smith, Roy Campbell (1898) [1893]. A History of the United States Navy, from 1775 to 1898. Vol. 1 (New ed.). New York: D. Appleton. OCLC 609036.

- Padfield, Peter (1968). Broke and the Shannon. London: Hodder and Stoughton. OCLC 464391714.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1883) [1882]. The Naval War of 1812 or The History of the United States Navy during the Last War with Great Britain (3rd ed.). New York: G.P. Putnam's sons. OCLC 133902576.

- Toll, Ian W. (2006). Six Frigates: The Epic History of the Founding of the US Navy. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-05847-6. OCLC 70291925.

- Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. London: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-86176-246-7. OCLC 181927614.

Further reading

[edit]- Dickon, Chris (2008). The Enduring Journey of the USS Chesapeake. Charleston, SC: History Press. ISBN 978-1-59629-298-7.

- Poolman, Kenneth (1962). Guns Off Cape Ann: The Story of the Shannon and the Chesapeake. Chicago: Rand McNally. OCLC 1384754.