Cape Fear (1962 film)

| Cape Fear | |

|---|---|

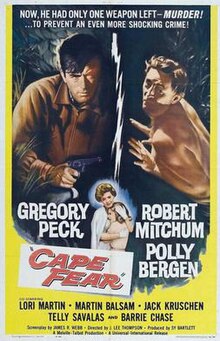

Film poster | |

| Directed by | J. Lee Thompson |

| Screenplay by | James R. Webb |

| Based on | The Executioners 1957 novel by John D. MacDonald |

| Produced by | Sy Bartlett |

| Starring | Gregory Peck Robert Mitchum Polly Bergen Lori Martin Martin Balsam Jack Kruschen Telly Savalas Barrie Chase |

| Cinematography | Sam Leavitt |

| Edited by | George Tomasini |

| Music by | Bernard Herrmann |

Production companies | Melville Productions Talbot Productions |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 106 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $1.8 million (US/Canada)[1] |

Cape Fear is a 1962 American psychological horror thriller film directed by J. Lee Thompson, from a screenplay by James R. Webb, adapting the 1957 novel The Executioners by John D. MacDonald. It stars Gregory Peck as Sam Bowden, an attorney and family man who is stalked by a violent psychopath and ex-con named Max Cady (played by Robert Mitchum), who is bent on revenge for Bowden's role in his conviction eight years prior. The film co-stars Polly Bergen and features Lori Martin, Martin Balsam, Jack Kruschen, Telly Savalas, and Barrie Chase in supporting roles.

Produced by Peck's company Melville Productions and distributed by Universal Pictures, the film includes several key cast and crew who had previously worked with director Alfred Hitchcock, including editor George Tomasini and composer Bernard Herrmann. J. Lee Thompson's direction was also strongly influenced by Hitchcock.

The film was released on June 15, 1962. It received positive reviews from critics, who highlighted Peck and Mitchum's performances. A remake of the same name was released in 1991, directed by Martin Scorsese and starring Nick Nolte and Robert De Niro in the lead roles. Peck, Mitchum, and Balsam all appeared as different characters in the remake.[2]

Plot

[edit]In Southeast Georgia, Max Cady is released from prison after serving an eight-year sentence for rape. He promptly tracks down Sam Bowden, an attorney whom he holds personally responsible for his conviction because Bowden interrupted his attack and testified against him. Cady begins to stalk and subtly threaten Bowden’s family, including his wife, Peggy, and 14-year-old daughter, Nancy. He kills the family dog, though Bowden cannot prove that Cady did it. A friend of Bowden, Police Chief Mark Dutton, attempts to intervene on Bowden's behalf, but he cannot prove Cady guilty of any crime.

Bowden hires private detective Charlie Sievers. Cady brutally rapes a young woman, Diane Taylor, when he brings her home, but neither the private detective nor Bowden can persuade her to testify. While Nancy is waiting in a car one day, Cady begins to walk near her, causing her to run and end up almost getting hit by a car. Bowden takes matters into his own hands by hiring three thugs to attack Cady and coerce him to leave town, but the plan backfires when Cady manages to fight back and get the better of all three. Cady's attorney vows to have Bowden disbarred.

Fearing for Peggy's and Nancy's safety, Bowden takes them to their houseboat in the Cape Fear region of North Carolina. In an attempt to trick Cady, Bowden makes it seem as though he has gone to Atlanta. He fully expects Cady to follow his wife and daughter, and he plans to kill Cady to end the battle. On a dark night, Bowden and local deputy Kersek hide in the swamp nearby, but Cady realizes that Kersek is there and drowns him, leaving no evidence of a struggle. Eluding Bowden and setting the houseboat adrift down the current, Cady first attacks Peggy on the boat, causing Bowden to go to her rescue. Meanwhile, Cady swims back to shore to attack Nancy. Bowden realizes what has happened, and also swims ashore.

The two men engage in a final fight on the riverbank. Bowden manages to grab his gun, which he had dropped, and shoots Cady, wounding and incapacitating him. Cady tells Bowden, "Finish the job", but Bowden decides to do the thing that Cady earlier told him would be unbearable – put him in prison for the rest of his life, to "count the years, the months, the hours". In the morning light, the Bowden family are together on a boat, traveling with police back to port.

Cast

[edit]- Gregory Peck as Sam Bowden

- Robert Mitchum as Max Cady

- Polly Bergen as Peggy Bowden

- Lori Martin as Nancy Bowden

- Martin Balsam as Mark Dutton

- Jack Kruschen as Dave Grafton

- Telly Savalas as Charlie Sievers

- Barrie Chase as Diane Taylor

- Paul Comi as Garner

- Page Slattery as Deputy Kersek

- Will Wright as Dr. Pearsell

In addition, Edward Platt, the future "Chief" on the television series Get Smart, and November 1958 Playboy Playmate centerfold Joan Staley make brief appearances as a judge and a waitress, respectively.

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Cornel Wilde acquired the rights to John D. MacDonald's novel The Executioners for $30,000 in 1958.[3] Gregory Peck had his own production company, Melville Productions, in partnership with Sy Bartlett, which had made The Big Country and Pork Chop Hill and they later purchased the rights. They planned to make it after The Guns of Navarone. Peck was impressed by J. Lee Thompson's work on that film and hired him for Cape Fear.[4] Peck said his goal was to make "first class professional entertainment intelligently done."[5] He was responsible for the title of the film, as he found the novel title "kind of a turn-off" and happened to find the Cape Fear region when looking for Atlantic coast locations.[6]

Casting

[edit]Telly Savalas was screen tested for the role, but later played private eye Charlie Sievers.[7] Robert Mitchum refused to play Max Cady when he was first offered the part, but eventually accepted it after Peck and Thompson delivered him flowers and a case of bourbon.[8]

Thompson wanted Hayley Mills, whom he had cast in Tiger Bay, to play the daughter, but Mills was unavailable.

Polly Bergen signed in December 1960. It was her first film in eight years.[9]

Filming

[edit]Principal photography of Cape Fear began on April 6 and ended in June 1961. Thompson envisioned the film in black and white, believing that shooting the film in color would lessen the atmosphere. As an Alfred Hitchcock fan, he wanted to have Hitchcockian elements in the film, such as unusual lighting angles, an eerie musical score, closeups, and subtle hints rather than graphic depictions of the violence Cady has in mind for the family. Hitchcock collaborators Robert F. Boyle and George Tomasini served as production designer and editor, and his regular composer Bernard Herrmann wrote the score.

The outdoor scenes were filmed on location in Savannah, Georgia; Stockton, California; and the Universal Studios backlot at Universal City, California. The indoor scenes were done at Universal Studios Soundstage. Mitchum had a real-life aversion to Savannah, where as a teenager, he had been charged with vagrancy and put on a chain gang. This resulted in a number of the outdoor scenes being shot at Ladd's Marina in Stockton, including the culminating conflict on the houseboat at the end of the movie.

The scene in which Mitchum attacks Polly Bergen's character on the houseboat was almost completely improvised.[citation needed] Before the scene was filmed, Thompson suddenly told a crew member: "Bring me a dish of eggs!" Mitchum's rubbing the eggs on Bergen was not scripted and Bergen's reactions were real. She also suffered back injuries from being knocked around so much. She felt the impact of the "attack" for days.[10] While filming the scene, Mitchum cut open his hand, leading Bergen to recall: "his hand was covered in blood, my back was covered in blood. We just kept going, caught up in the scene. They came over and physically stopped us."[11]

In the source novel The Executioners, by John D. MacDonald, Cady was a soldier court-martialed and convicted on then Lieutenant Bowden's testimony for the brutal rape of a 14-year-old girl. The censors stepped in, banned the use of the word "rape", and stated that depicting Cady as a soldier reflected adversely on U.S. military personnel.[citation needed]

Music

[edit]Bernard Herrmann, as often in his scores, uses a reduced version of the symphony orchestra. Here, other than a 46-piece string section (slightly larger than usual for film scores), he adds four flutes (doubling on two piccolos, two alto flutes in G, and two bass flutes in C) and eight French horns. No use is made of further wind instruments or percussion.[12]

In his 2002 book A Heart at Fire's Center: The Life and Music of Bernard Herrmann, Stephen C. Smith writes:

"Yet Herrmann was perfect for Cape Fear ... Herrmann's score reinforces Cape Fear's savagery. Mainly a synthesis of past devices, its power comes from their imaginative application and another ingenious orchestration ... a rehearsal for his similar orchestration on Hitchcock's Torn Curtain in 1966. Like similar 'psychological' Herrmann scores, dissonant string combinations suggest the workings of a killer's mind (most startlingly in a queasy device for cello and bass viols as Cadey prepares to attack the prostitute). Hermann's prelude searingly establishes the dramatic conflict: descending and ascending chromatic voices move slowly towards each other from their opposite registers, finally crossing–just as Boden and Cadey's [sic] game of cat-and-mouse will end in deadly confrontation."[13]

Release

[edit]Censorship

[edit]Although the word "rape" was entirely removed from the script before shooting, the film still enraged the censors, who worried that "there was a continuous threat of sexual assault on a child." To accept the film, British censors required extensive editing and deleting of specific scenes.[14]

After making around 6 minutes of cuts, the film still nearly garnered a British X rating (meaning at the time, "Suitable for those aged 18 and older", not necessarily meaning there was sexually explicit or violent content).[citation needed][15] Thompson said he had to make 161 cuts; the censor argued it was fifteen main cuts but admitted they took 5 minutes. The censor said this was primarily because the film involved threat of sexual assault against a child.[16]

Critical response

[edit]Upon its release, the film received positive but cautious feedback from critics due to the film's content. On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 92% of 25 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 7.9/10. The website's consensus reads: "An exemplary thriller powered by Robert Mitchum's chilling performance and Bernard Herrmann's sinister score, Cape Fear seethes with perfectly modulated tension."[17]

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times praised the "tough, tight script", as well as the film's "steady and starkly sinister style." He went on to conclude his review by saying, "this is really one of those shockers that provokes disgust and regret."[18] The entertainment-trade magazine Variety reviewed the film as "competent and visually polished", while commenting on Mitchum's performance as a "menacing omnipresence."[19]

Home media

[edit]Cape Fear was first made available on VHS on March 1, 1992. On May 14, 1992, it was released on laserdisc. It was later re-released on VHS, as well as DVD, on September 18, 2001. The film was released onto Blu-ray on January 8, 2013. It contains production photos and a "making-of" featurette.[20]

Remake

[edit]A remake of the same name was released in 1991, attributing both MacDonald's novel and Webb's 1962 screenplay as source material. Directed by Martin Scorsese and written by Wesley Strick, the film stars Nick Nolte as Bowden, Robert De Niro as Cady, Jessica Lange as Bowden's wife (renamed 'Leigh') and Juliette Lewis as his daughter (renamed 'Danielle').

Gregory Peck, Robert Mitchum, and Martin Balsam all make cameo appearances, and Bernard Herrmann's original score was adapted and re-orchestrated by Elmer Bernstein.

The film makes several notable changes to the story, namely by changing Sam Bowden to Cady's former defense attorney, who secretly and deliberately sabotaged his client's case to ensure a conviction. Cady dies during the film's climax, after the houseboat sinks. The remake also combines Charlie Sievers and Deputy Kersek into a single character - Claude Kersek (played by Joe Don Baker).

Legacy

[edit]Although it makes no acknowledgement of Cape Fear, the episode "The Force of Evil" from the 1977 NBC television series Quinn Martin's Tales of the Unexpected uses virtually the same plot, merely introducing an additional supernatural element to the released prisoner.[21][22]

The film and its remake serve as the basis for the 1993 The Simpsons episode "Cape Feare" in which Sideshow Bob, recently released from prison, stalks the Simpson family in an attempt to kill Bart. The episode, and both films, serve as inspiration for Anne Washburn's play Mr. Burns, a Post-Electric Play.

In April 2007, Newsweek selected Cady as one of the 10 best villains in cinema history. Specifically, the scene where Cady attacks Sam's family was ranked number 36 on Bravo's 100 Scariest Movie Moments in 2004.[23]

A consumer poll on the Internet Movie Database rates Cape Fear as the 65th-best trial film, although the trial scenes are merely incidental to the plot.[24]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2001: AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – #61[25]

- 2003: AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Big Rental Pictures of 1962". Variety. January 9, 1963. p. 13. Please note these are rentals and not gross figures

- ^ Kirsten Thompson, Cape Fear and Trembling: Familial Dread; In Literature and Film: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Film Adaptation, Edited by Robert Stam, Alessandra Raengo, Blackwell Publishing, 2005, ISBN 0631230556 (pp.126-147)

- ^ "New York Sound Track". Variety. March 26, 1958. p. 7. Retrieved October 26, 2024 – via Archive.org.

- ^ PECK'S FILM FIRM PLANS 3 PROJECTS: Star and Sy Bartlett List 2 Comedies and Drama -- 'Apartment' Here Today By HOWARD THOMPSON. New York Times June 15, 1960: 50.

- ^ Peck Wants to Make Film Classic: PECK FILM Hyams, Joe. Los Angeles Times April 15, 1961: A6.

- ^ https://www.starnewsonline.com/story/news/2021/09/28/cape-fear-film-connection-cape-fear-river/8334452002/

- ^ p.283 Chibnall, Steve J. Lee Thompson Manchester University Press, 2000

- ^ Honeycutt, Kirk (April 9, 1978). "Robert Mitchum Rolls Merrily on Despite the Vehicles". The New York Times.

- ^ GABLE'S LAST FILM SLATED HERE FEB.1: 'Misfits' Is Due at Capitol -- 3 Other Premieres Set -- Hudson, Doris Day Cited By HOWARD THOMPSON. New York Times December 31, 1960: 10.

- ^ Robert Mitchum The Reluctant Star (DVD). Harrington Park: Janson Media. 2009.

- ^ Stafford, Jeff. "Cape Fear". Turner Classic Movies. Turner Entertainment Networks. Retrieved October 26, 2024.

- ^ Bill Wrobel: Cape Fear, score rundown analysis

- ^ Smith, Steven C. (May 31, 2002). A Heart at Fire's Center: The Life and Music of Bernard Herrmann - Steven C. Smith - Google Books. University of California Press. p. 252. ISBN 0-520-22939-8. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ^ Why Cape Fear can't go on Author: Cecil Wilson Date: Thursday, May 3, 1962, Publication: Daily Mail p 6

- ^ Film chief censors Our 'Erb Author: Barry Norman Date: Wednesday, June 13, 1962, Publication: Daily Mail p 3

- ^ Why we cut Cape Fear—by the film censors Author: Barry Norman Date: Friday, June 22, 1962, Publication: Daily Mail p 3

- ^ "Cape Fear". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (April 19, 1962). "Screen: Pitiless Shocker:Mitchum Stalks Peck in 'Cape Fear'". The New York Times. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ "Cape Fear". Variety. December 31, 1961. Retrieved October 26, 2024.

- ^ Seller, Ryan (October 12, 2012). "Cape Fear (1962) Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ John Kenneth Muir's Reflections on Cult Movies and Classic TV: CULT TV FLASHBACK # 54: Quinn Martin's Tales of the Unexpected (1977)

- ^ Muir, John Kenneth, Terror Television: American Series 1970-1999, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2001. ISBN 978-0-7864-3884-6. Not paginated.

- ^ "The 100 Scariest Movie Moments". Bravo.tv.com. Archived from the original on October 30, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ Cape Fear at Internet Movie Database.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Bergman, Paul; Asimow, Michael. (2006) Reel justice: the courtroom goes to the movies (Kansas City: Andrews and McMeel). ISBN 0-7407-5460-2; ISBN 978-0-7407-5460-9; ISBN 0-8362-1035-2; ISBN 978-0-8362-1035-4.

- Machura, Stefan and Robson, Peter, eds. Law and Film: Representing Law in Movies (Cambridge: Blackwell Publishing, 2001). Thain, Gerald J., "Cape Fear, Two Versions and Two Visions Separated by Thirty Years." ISBN 0-631-22816-0, ISBN 978-0-631-22816-5. 176 pages.

External links

[edit]- Cape Fear at IMDb

- Cape Fear at the TCM Movie Database

- Cape Fear at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Cape Fear at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1962 films

- 1960s American films

- 1960s English-language films

- 1960s legal films

- 1960s horror films

- 1960s psychological thriller films

- American black-and-white films

- American films about revenge

- American legal films

- American legal thriller films

- American horror thriller films

- American psychological thriller films

- Film censorship in the United Kingdom

- Films about families

- Films about home invasion

- Films about rape in the United States

- Films about stalking

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on thriller novels

- Films based on works by John D. MacDonald

- Films directed by J. Lee Thompson

- Films produced by Gregory Peck

- Films scored by Bernard Herrmann

- Films set in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Films set in North Carolina

- Films set on boats

- Films shot in California

- Films shot in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Films shot in Savannah, Georgia

- Films with screenplays by James R. Webb

- Melville Productions films

- Southern Gothic films

- Universal Pictures films

- English-language horror films

- English-language thriller films